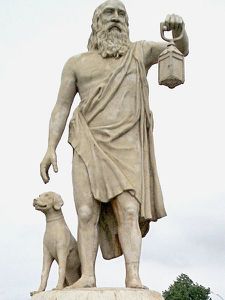

“I am Alexander the Great,” said the monarch. Curious to see the one who exhibited such haughty independence of spirit, Alexander went in search of him and found him sitting in his tub in the sun. Plutarch relates that Alexander, when at Corinth, receiving the congratulations of all ranks on being appointed to command the army of the Greeks against the Persians, missed Diogenes among the number, with whose character he was acquainted. Diogenes executed this trust with so much judgment and fidelity that Xeniades used to say that the gods had sent a good genius to his house.ĭuring his residence at Corinth, an interview between him and Alexander is said to have taken place. On their arrival at Corinth, Xeniades gave him his freedom and committed to him the education of his children and the direction of his domestic concerns. When the auctioneer asked him what he could do, he said, “I can govern men therefore sell me to one who wants a master.” Xeniades, a wealthy Corinthian, happening at that instant to pass by, was struck with the singularity of his reply and purchased him. In his old age, sailing to Aegina, he was taken by pirates and carried to Crete, where he was exposed to sale in the public market. It cannot be doubted, however, that Diogenes practiced self-control and a most rigid abstinence – exposing himself to the utmost extremes of heat and cold and living upon the simplest diet, casually supplied by the hand of charity. But no notice is taken of this by other ancient writers who have mentioned this philosopher. This famous “tub” is indeed celebrated by Juvenal it is also ridiculed by Lucian and mentioned by Seneca. It is probable, however, that this was only a temporary expression of indignation and contempt, and that he did not make it the settled place of his residence. He asked a friend to procure him a cell to live in when there was a delay, he took up abode in a pithos, or large tub, in the Metroum. He wore a coarse cloak, carried a wallet and a staff, made the porticoes and other public places his habitation, and depended upon casual contributions for his daily bread. Renouncing every other object of ambition, he distinguished himself by his contempt of riches and honors and by his invectives against luxury. The Cynics became some sort of jesters, accepted at the royal courts because their criticism was essentially harmless.ĭiogenes fully adopted the principles and character of his master. His philosophy gained some popularity because he focused upon personal integrity, whereas men like Plato and Aristotle had been thinking about man’s life and honor as member of a city state – a type of political unit that was losing importance in the age of Alexander the Great. Like his master, Diogenes refrained from luxury and often ridiculed civilized life. Human culture, however, is dominated by things that prevent simplicity: money, for example, and our longing for status.

We are happiest when our life is simplest, which means that we have to live in accordance with nature – just like animals. The essential point in this world-view is that man suffers from too much civilization. Diogenes calmly bore the rebuke and said, “Strike me, Antisthenes, but you will never find a stick sufficiently hard to remove me from your presence, while you speak anything worth hearing.” The philosopher was so much pleased with this reply that he at once admitted him among his scholars.īoth Antisthenes and Diogenes are called the founder of the school that is known as Cynicism. Antisthenes at first refused to admit him into his house and even struck him with a stick. Here he attached himself, as a disciple, to Antisthenes, who was at the head of the Cynics. His father, Icesias, a banker, was convicted of debasing the public coin, and was obliged to leave the country or, according to another account, his father and himself were charged with this offense, and the former was thrown into prison, while the son escaped and went to Athens.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)